v:* {behavior:url(#default#VML);}

o:* {behavior:url(#default#VML);}

w:* {behavior:url(#default#VML);}

.shape {behavior:url(#default#VML);}

p

p

2

64

2015-04-22T22:20:00Z

2015-04-22T22:20:00Z

4

2572

14665

Microsoft

122

34

17203

14.0

Clean

Clean

false

false

false

false

EN-US

JA

X-NONE

General methods of searching for court cases

It would be very helpful to be able to mine a comprehensive database of all on-going and completed U.S. court cases. For instance, it might have been useful to learn about how lawsuits were being filed alleging car accidents caused by faulty brakes or for research misconduct.

While it might be possible to type “faulty brakes” and “lawsuit” into a search engine, by the time a court case can be found in general Internet searches, it most likely is because it has had a judicial opinion released by the court, or news stories about the case have already been published.

What would be better, particularly for data mining, is to be able to search the documents in a court case, such as the complaint, as soon as they are filed at the courthouse.

Searching Court Dockets vs. Case Law

Let’s say we want to find all legal cases filed that have to do with NIH grant fraud. By that we mean not only those cases for which a judge has already issued a judicial opinion or a jury has come to a verdict, but also those “pending” cases, i.e. those “awaiting decision or settlement” (OED). “Case law”, in contrast, is essentially restricted to judicial opinions that interpret existing law and that can form a legal precedent for other courts.

Case law is often “published”, and is more readily available than case dockets. But documents within case dockets, such as the complaint, which is filed at the start of the case, can provide a much earlier notice of the existence and topic of pending cases for which no judicial opinion has yet been published.

PACER is the underlying foundation for electronic court dockets

Publicly available, online case documents in the U.S. are most widely available through PACER, which stands for “Public Access to Court Electronic Records”. PACER contains case docket sheets and the documents referenced in those docket sheets, in particular for federal courts. So PACER is potentially very useful database from which to find pending cases.

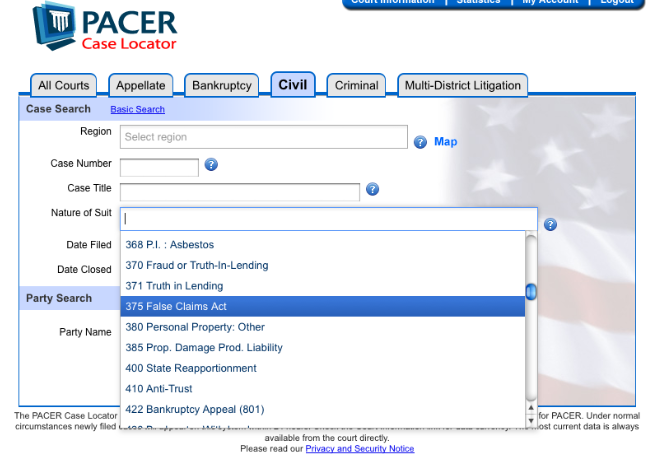

Data mining implies searching for and finding cases not already known to the searcher. PACER can be mined for unknown cases only by using the case category structure PACER has created. For example, cases can be found under “370 Fraud or Truth in Lending” or “375 False Claims Act”.

Even with a category structure, PACER’s users are dependent on the various courts in the U.S. to properly categorize the cases that they submit to PACER. And even if cases are submitted and the correct categories applied, needless to say, there is no category for “faulty brakes”.

PACER’s broad categories also often lead to a large number of irrelevant results. Unless the search term of interest is in a case name, it won’t be found by a text search of cases downloaded by a category search. Quite a bit of additional manual labor can be spent to go to each case found in a PACER category search to look for terms of specific interest in a document, such as the complaint, to learn if the case is really relevant.

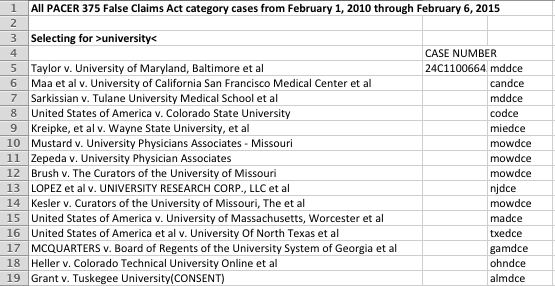

Of even greater concern, negative results can be hard to interpret without knowing something about the quality of the database. For example, we obtained all PACER 375 False Claims Act (FCA) category cases from February 1, 2010 through February 6, 2015. We were interested in finding any evidence of biomedical research misconduct FCA cases filed during that time. Since many of those cases name a university as the defendant, we selected for all FCA results during the period of interest that named a university as a party, or more exactly, had the term “university” in the case title. The resulting cases are shown in the following table.

The complaint for each of the above cases was then manually downloaded from PACER and examined to determine the basis of the suit. The suits involved primarily Medicare and other billing fraud, but also a fraudulent NIH effort claim as well as sexual/racial harassment and retaliation claims. Not a single FCA case involving data fabrication, falsification, or plagiarism was found. The latter would be a very surprising state of affairs if true for the entire U.S., since it would suggest that no research misconduct case had been filed and unsealed during that five year period. A text search would allow a much more robust assessment of the quality of the PACER categorization, e.g. we could look for the terms “NIH” OR “National Institutes of Health” AND “research misconduct” in the complaint and other documents within the docket.

According to a PACER representative, (February 4, 2015), text searches are not an option, either of published judicial opinions or for any other documents in a court docket: “PACER does not offer the ability to search by keyword”. Additionally:

“PACER’s function is to provide access to known cases that can be found with basic case identifiers. For example, PACER clients can search by circuit, region, date, and/or case number. It is not intended as a research tool.” [Emphasis added].

Databases for legal research – do any allow user supplied text searches?

One free option for legal research is offered by Google Scholar. Google Scholar allows a full text search to obtain judicial opinions – but not necessarily any other documents associated with a legal case. Our searches did not reveal any U.S. court dockets in Google Scholar. With respect to case law:

“Currently, Google Scholar allows you to search and read published opinions of US state appellate and supreme court cases since 1950, US federal district, appellate, tax and bankruptcy courts since 1923 and US Supreme Court cases since 1791. In addition, it includes citations for cases cited by indexed opinions or journal articles which allows you to find influential cases (usually older or international) which are not yet online or publicly available.” (https://scholar.google.com/intl/en/scholar/help.html#coverage; February 12, 2015)

Another option, which might be more complete, is offered by FastCase, which permits string searches of a great deal of U.S. case law (i.e. judicial opinions; see above). While FastCase is considered among the less expensive yet still attorney-quality case law options at $99/month, it does not provide access to any other documents in a court docket, such as the complaint.

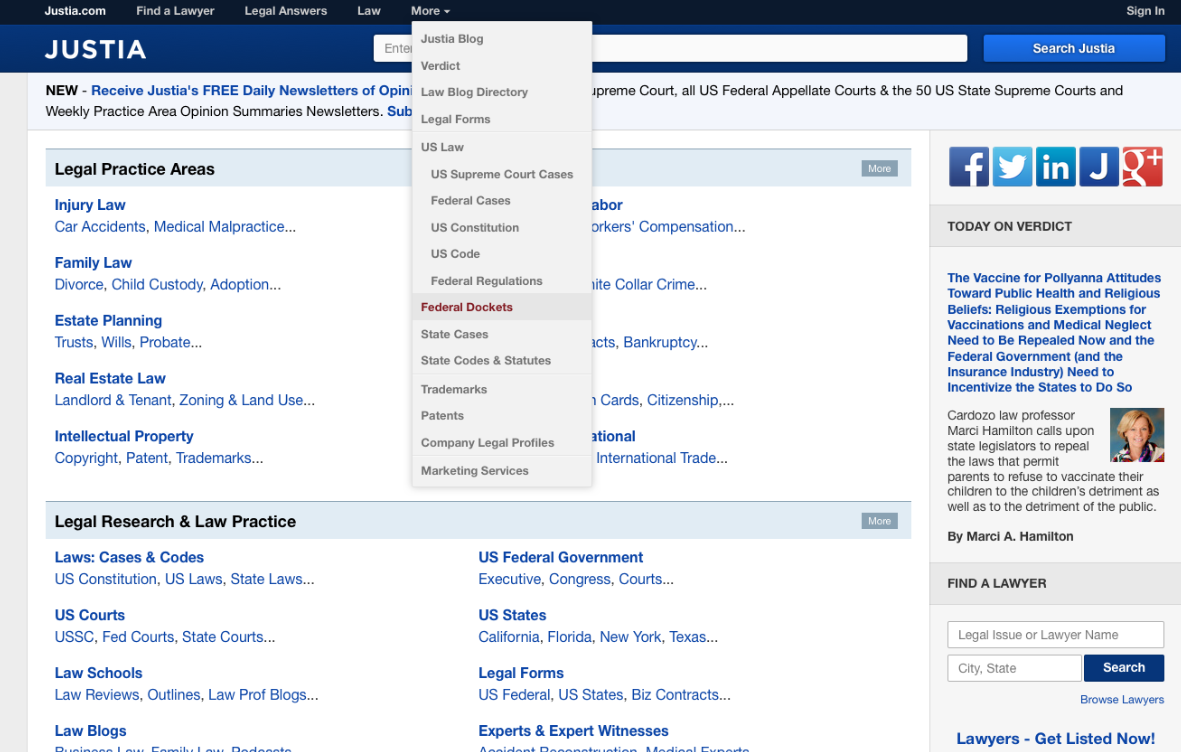

Several other Internet-based products are more obvious “front ends” for PACER. These include PACERPro, Justia, and Plainsite.

Justia offers many legal support services, but in terms of docket data mining, it appears to be a close variant of PACER, as shown in test searches of its Federal Dockets:

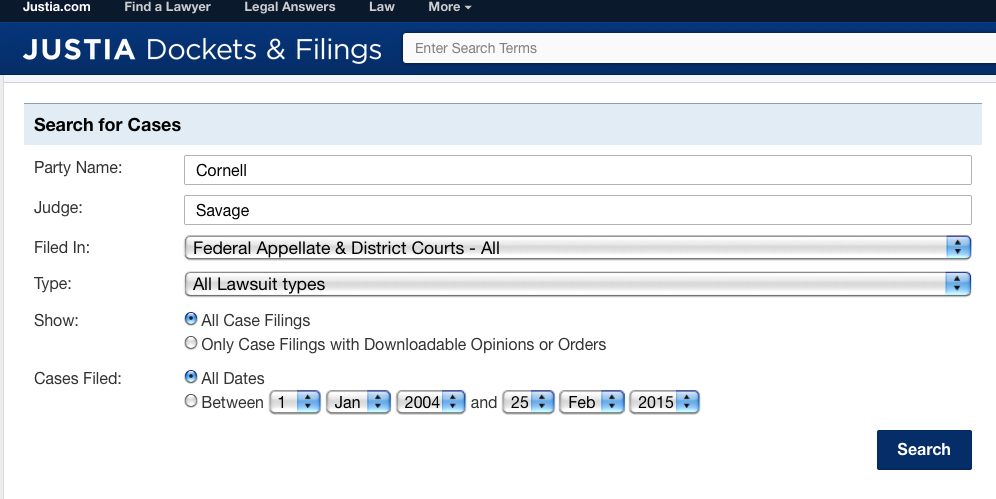

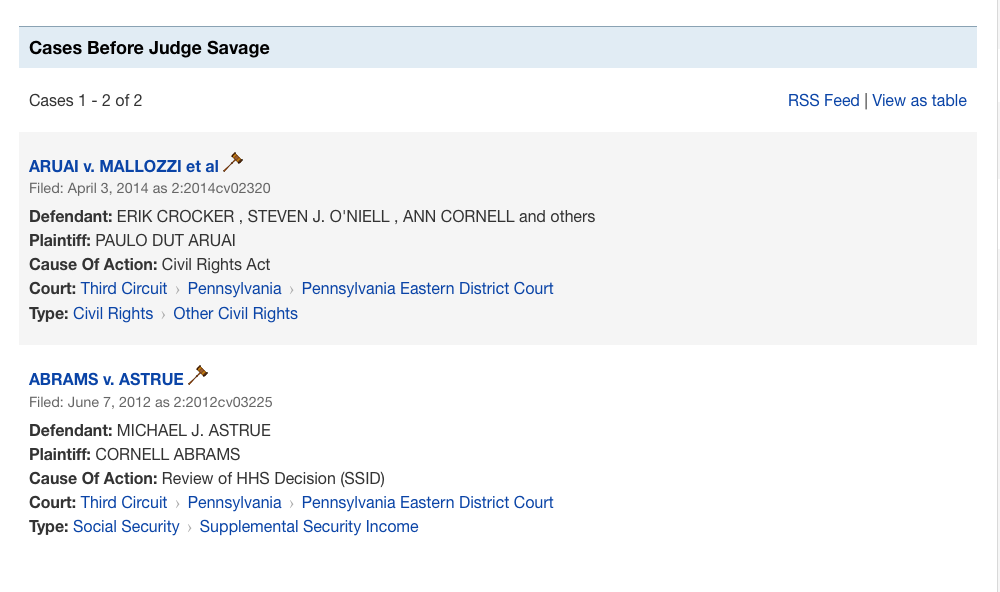

Unfortunately, our tests of Justia to find cases in which we knew the party name, or also even the judge’s name, failed to produce a complete set of results. For example, the following search failed to show a known case involving defendant Cornell University and presiding judge Timothy J. Savage, though two other cases involving Judge Savage and parties named Cornell were found:

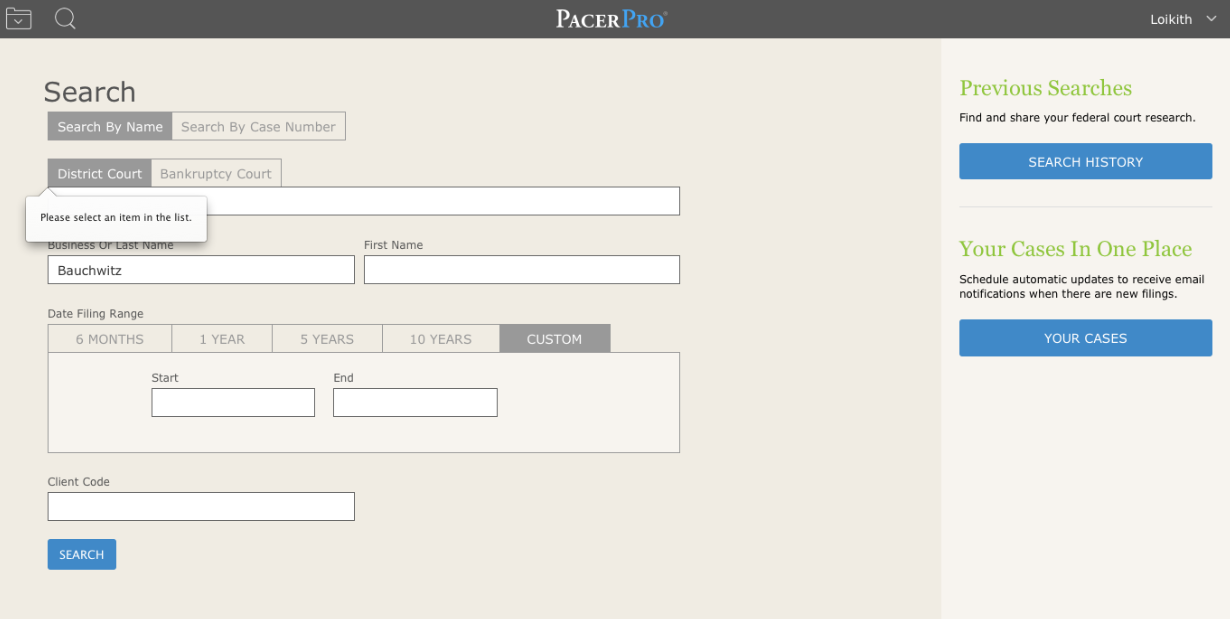

PACERpro apparently requires foreknowledge of case information such as the court, i.e. it does not even allow searches across all courts based solely on party name:

Therefore, PACERPro would not qualify as a data mining tool that relies on text-based searches.

Plainsite comes in two forms, “Pro” and “Pro Se”. The site was not clear in specifying exactly who is appropriate to use which version of the site (February 16, 2015). For example, in the initial sign-up screen to choose a level of service, the site says regarding the Pro Se service:

“PlainSite Pro Se. Tools for non-professionals, affordably priced at $9.99 per month”.

But in the following screen for Pro Se, it seems to warn:

“Using a PlainSite Pro Se account if you are not actually a pro se litigant will cause your account to be de-activated and/or re-billed at the Pro rate”.

So we had to wonder whether the Pro Se version was for any non-(legal) professional, or only for pro se litigants.

We also found that the payment terms were unclear: “By clicking “Go” below, I certify that I authorize a non-refundable charge of $99.00 to be made to the above card monthly.” The underlined words were not links for us. There was no statement that the charges could be canceled, or that they were for a minimum of one year.

Plainsite Support was responsive to our questions. We received the following comments regarding the points raised above (March 6, 2015):

“Your feedback is appreciated and we will attempt to clarify the distinction between Pro and Pro Se in the future. Pro Se is for pro se litigants. Non-legal professionals who are pro se in a case can use Pro Se. Non-legal professionals who are making money by using PlainSite must use Pro. Non-legal professionals who are not making money by using PlainSite but are also not pro se, and just doing personal research, can use pro se–which I think is the unclear and potentially confusing part. … [Therefore]

… if you are profiting from your use of PlainSite you should sign up for the Pro version. If you want to cancel you can do so at any time. Both subscriptions allow you to upload and/or request documents.” [Emphasis added.]

As to the capabilities, we found that Plainsite’s baseline presentation was also a docket sheet without the actual documents; however, Plainsite now shows the docket sheets in reverse chronological order relative to the entry dates.

Most importantly, we could not find a known index test case by searching for a defendant’s name that appears in the case title. In fact, it required quite a bit of preexisting knowledge to find the case at all. When the docket was found, it had several pieces of incorrect information, such as the names of the law firms involved. Therefore, it may be that it is possible for Plainsite data to become corrupted during or after its transfer from PACER.

We conclude that, essentially without exception, low cost databases based on PACER are no more searchable by text than PACER itself. Such limited databases are hardly useful for serious data mining! This begs the question: do any legal research sites have all-inclusive databases?

More expensive commercial options that have dockets

Three of the major firms that provide legal information have products that allow text searches of dockets, but the presence of documents associated with those dockets is dependent on prior users having obtained the documents themselves.

For example, a product information web page about the Bloomberg Law Dockets product makes the following enticing statement”

“Employ our unrestricted and powerful search and alert capabilities for court dockets and filings that are loaded on the system.”

A Bloomberg Law representative clarified, however, that Boolean searches of their dockets and associated documents can be performed with keywords – but only on the docket documents that other clients have purchased (January 26, 2015). One exception exists. Bloomberg Law has an agreement with the Delaware Court of Chancery to upload all the documents filed in that court within hours, with the exception of transcripts. (Lee Passacreta, April 15, 2015).

LexisNexis Courtlink representatives have confirmed that the documents available on their sites for searching are also only those that have been previously purchased by clients (February 12, 2015).

WestLawNext has a few products that also allow text searches of some docket material. The most relevant to data mining of documents in court dockets is called, appropriately enough, “Dockets”. The Dockets product does allow a search of all the words in docket sheets, but as with the products from other companies referenced above, the only documents present in the docket are those that other users have already requested. Furthermore, in real-time tests of the product, we were unable to find several control cases which were found when looking for judicial opinions on other platforms.

Thus, the only difference from the PlainSite model is that the former allows subscribers to voluntarily provide case-related documents, while Bloomberg Law, LexisNexis, and WestLawNext all provide case documents that were purchased by others. Obviously, such databases are not likely to be adequately complete for data mining.

Westlaw does offer a solution for learning about new cases relevant to user-provided search terms. The service is called CourtWire. However, Courtwire is actually the opposite of a searchable database. CourtWire employs people at various court locations throughout the U.S. who, in effect, manually check court filings and generate reports for users. Not surprisingly, this service is relatively expensive, but is one of the few that allows users to learn about new cases with something like custom keywords.

Will there ever be text searches of the PACER court database?

In summary, there does not currently appear to exist an all-inclusive database of U.S. court case documents with text string searching capacity. This resource would be undeniably valuable.

Not surprisingly, we wondered why such an obvious product had not yet been made available from some source. There were rumors in 2013 from company representatives that WestLaw would work with Google to provide such an all-inclusive, searchable database. But by this year, 2015, Westlaw representatives could find no further information on such a collaboration.

Ultimately, it seems that PACER is the well-spring of most of the various electronic case document products. Therefore, we posed additional questions to the Administrative Office of the United States Courts, the agency which manages PACER “in accordance with the policies of the Judicial Conference, headed by the Chief Justice of the United States.” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/PACER_(law)).

Charles Hall, a spokesman for the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts, provided the following information to us after spending some time vetting the responses (April 20, 2015):

1. Are there plans to provide a text search capability to the case documents in PACER?

“The judiciary is in the process of migrating its Case Management and Electronic Case Filing System (CM/ECF) to CM/ECF’s NextGen.

In developing the scope of NextGen, the judiciary reached out to a wide group of interested parties. Requests for upgrades included these areas: single sign-on, enhanced search capabilities, batch data transfer, and customizable reports.

The judiciary is prioritizing requests and will develop a schedule for delivery of the new system. Improved case searchability remains under consideration as part of that process.” [Emphasis added.]

2. 2. If there are, what national standards will be employed for data input by the various courts that contribute case documents? For example, will documents be required to have text present in searchable form, rather than as images? What other database quality control measures are planned?

“As a national read-only window displaying electronic court filings, PACER is dependent on what documents actually are filed into individual courts’ CM/ECF databases by litigants and lawyers. Filers may only attach PDF documents, but at present, there is no requirement that the text be in searchable form, so the public has as much, or as little, search capability as the original document allows.

The only text-searchability requirement involving federal court documents is a requirement, under the E-Government Act, that the substance of written opinions be publicly available in a text-searchable format. This requirement is met by each court having a written opinions report in PACER, by having opinions available on court web sites, and by making opinions available on the Government Printing Office’s FDsys system.

To protect the integrity of court records in CM/ECF, PDFs are not modified by the courts after they are filed by litigants.” [Emphasis added.]

3. If there are not such plans, is there a specific policy reason why not?

“Federal courts historically have broad latitude on many administrative matters, so that they can make decisions based on local needs, and in this context, separate CM/ECF databases enable courts to retain control over the records of their cases.”

At least we have our answers from the horse’s mouth, the “horse” in this case ultimately being the U.S. Judicial Conference. From what we were told, we can still hope that the control that individual courts in the U.S. have over their records can be brought into line with new federal standards that might greatly enhance the ability to mine records deposited in the federal court dockets.

For the time being, text searching of U.S. court documents still has room for improvement in terms of comprehensive access and availability. Data mining of all U.S. court dockets and their associated documents ultimately should provide the public with a much more accurate assessment how various areas of litigation are being handled.

Lee & Bauchwitz