Publications as an alternative or supplement to CTgov?

ClinicalTrials.gov (CTgov) states that links are automatically provided in the Results tab for any publication [in PubMed] that contains the NCT identifier for the trial.

Unfortunately, we can see from the survey of Fragile X Syndrome (FXS) trials on CTgov on the prior page, that no clinical trial outcome data or results were presented using links to research articles for the three trials that had any results presented at all.

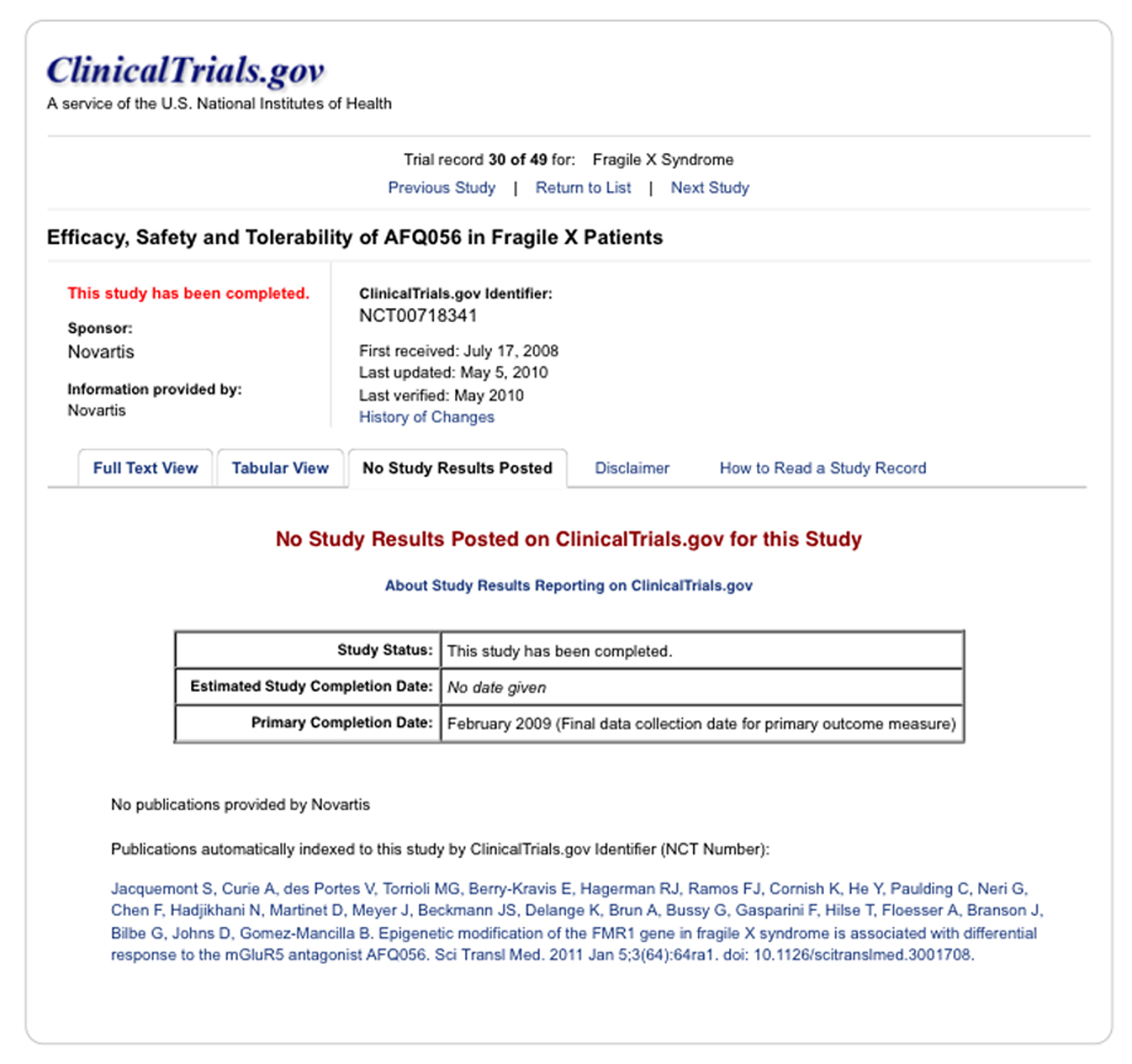

CTgov does contain a link to a paper discussing the results of a phase 2 clinical trial of the Novartis mGluR5 antagonist AFQ056, aka mavoglurant (trial number NCT00718341):

However, this paper actually analyses a precursor trial to the one of interest.

In a further attempt to get additional data, results, and interpretations of clinical trials presented on CTgov, searches can be made using PubMed, and the general Internet.

PubMed is an online public search engine of the biomedical and life science research articles found in the Medline database, which is also a product of NLM. PubMed is published by the National Library of Medicine (NLM), which is a component of the NIH.

While our primary goal is to find research publications about specific studies of interest, it can also be useful to review related material on the website of sponsors, interested foundations, and news sites, among others.

Here, an illustration of additional material found for the three FXS trials which did have CTgov outcome data is presented, in particular to determine whether more detail is provided and whether information about follow up (mostly phase “3”) trials is available.

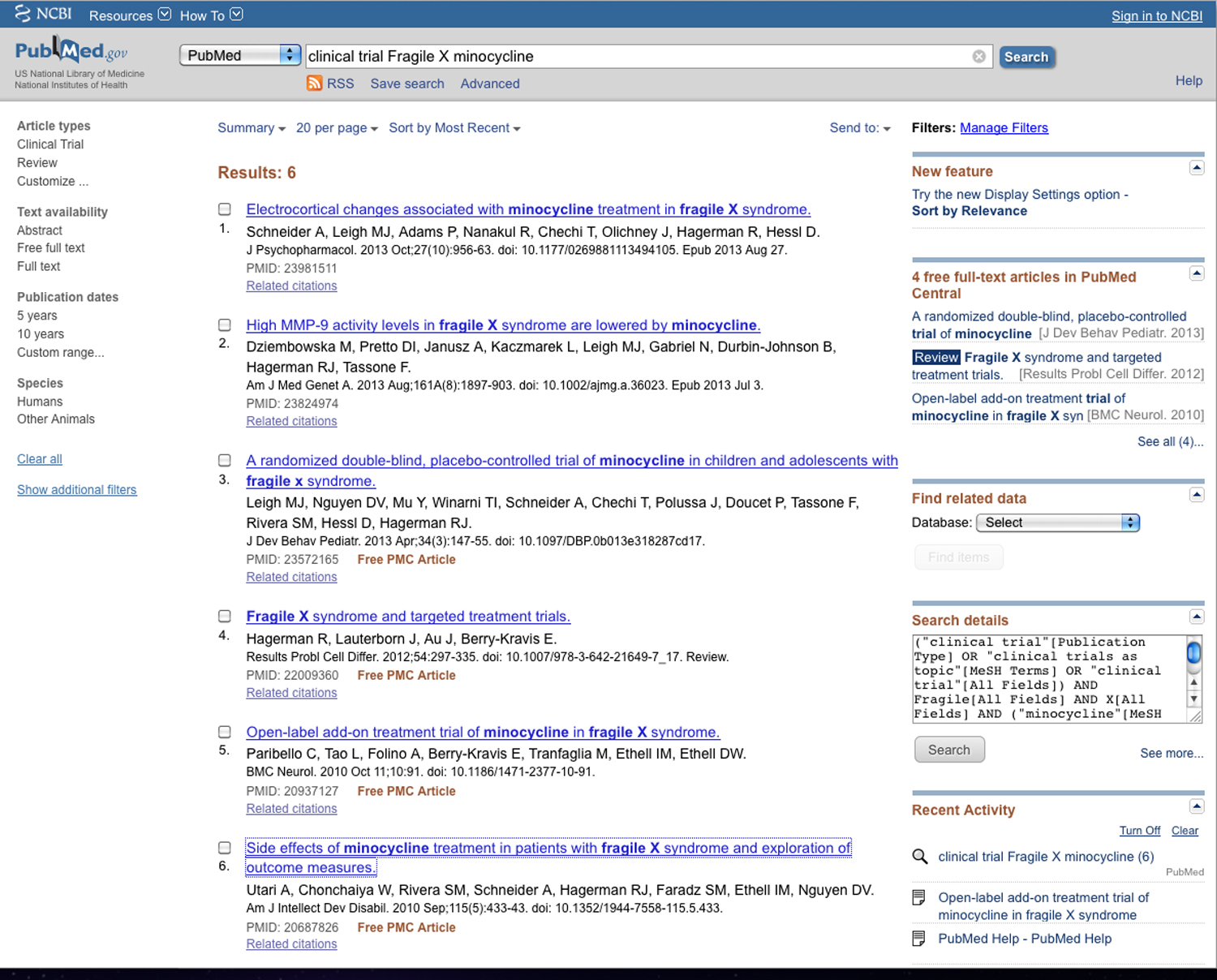

1. >clinical trial Fragile X minocycline<

Despite the clearly positive published assessments from the phase 2 trial investigators for the FXS/minocycline clinical trial NCT 01053156 (see prior page), there is as yet (April 17, 2015) no registration of a phase 3 clinical trial for minocycline on CTgov. Since registration of most interventional trials on CTgov is mandatory (more detail will be provided in a following post), the absence of any mention of a phase 3 trial for minocycline in FXS gives a very reasonable certainty that such a trial has not started in the U.S.

A search of PubMed for the terms between the angle brackets at 1, above, shows 6 results:

In looking through the list of 6 publications found on PubMed, a publication by Leigh et. al. in 2013 concerns the phase 2 trials which presented results on CTgov. A search of that paper, however, does not show the clinical trial identifier, NCT01053156, which probably explains why CTgov did not find the article and produce a link to it. Most likely, this was the result of an oversight by the authors.

Much more detailed information was provided in the Leigh2013 research report than in the CTgov summary, such as the following statement about the statistical analysis:

“The model to assess efficacy was a linear mixed-effect (LME) model for repeated measures in a minocycline/placebo, two-period cross-over trial. The model terms included treatment, period, and baseline measurement if available. … The study was designed to achieve 85% power to detect a treatment effect size of 0.55 at level alpha = 0.025 in a crossover design. The required sample size is 74 but funding limitations limited the number to 66 who were randomized.”

Furthermore, it was noted,

“Although statistically significant, the CGI-I improvement (average of 0.5 points) was modest. The average VAS scores were rated as more improved on minocycline than placebo, but the difference was not significant.”

With respect to the longer-term goal of these posts, i.e. to compare the tests performed on subjects with those given to the preclinical animals, note that the primary results presented are subjective assessments from caregivers, and not the results of more objective “tests”:

“The CGI-I utilizes history from primary caregivers and incorporates it into a seven step clinical rating for follow up throughout treatment, from 1 “very much improved” to 7 “very much worse”. A VAS is used to represent a caregiver’s assessment of given behaviors, which were chosen by the parents. Caregivers marked a 10 cm horizontal line representing a visual continuum of each behavior from “worst behavior” to “behavior not a problem.”

There were, however, results deduced from a post hoc analysis of the VAS data:

“When the VAS behaviors were grouped by behavior category, minocycline was associated with a significantly greater improvement in anxiety and mood related behaviors (minocycline 5.26 cm ±0.46 cm, placebo 4.05 cm±0.46cm; p 0.0488).” [Emphasis added.]

At least one test was performed to measure changes in cognitive function that could be related to IQ: the Expressive Vocabulary Test Second Edition (EVT-2). “The EVT-2 assesses language development through a participant’s one word synonym response to visual stimuli”. However, there was no effect of minocycline seen.

While the lack of improvement on scores of cognition might not be very surprising given the short duration of the trial (among other factors), it is also possible that the improvement in anxiety and mood were not specific to FXS either. Unfortunately, no statements were made in the article with respect to whether minocycline had been assessed for anxiolytic or mood altering effects in other, non-FXS populations, nor just how much time was necessary in other studies to see EVT-2 responses.

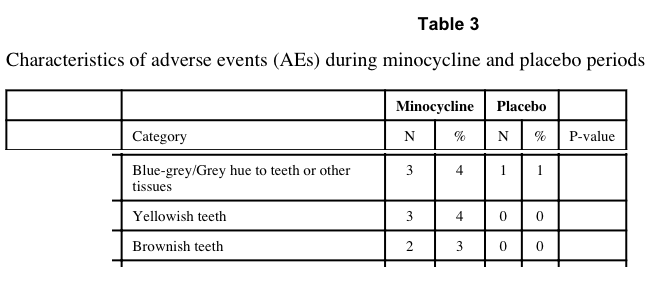

Finally, there was at least one effect of the drug that might have led to an unintended unblinding effect, namely that the minocycline antibiotic was able to cause a discoloration of the teeth:

“Of note, brown and yellow tooth discolorations were reported during the minocycline trial period for 5 patients. However, most of these discolorations resolved, and their significance is unclear as the tooth staining associated with tetracyclines is typically permanent.”

The data presented suggest that there may have been additional discoloration effects of the minocycline that could have affected the blinding of the study:

The obvious question is whether the potential effect of such discoloration effects was presented, i.e. would any significance claimed in the results have been retained had the above 8 minocycline results been removed?

No direct statement was made with respect to whether removal of the 5-8 subjects whose tooth or other tissue coloration by the drug might have caused an unblinding and thereby any effect on statistical significance. Rather, it was stated that there was no difference in such side effects, despite the apparent appearance of tooth staining in eight subjects while on minocycline compared to in only a single subject while on placebo:

“Another weakness is that drug-related side effects have the potential to unblind both subjects and investigators; for minocycline, these include teeth graying and photosensitivity, however there was no significant difference in these effects or any other side effects between the two study groups.” [Emphasis added.]

The CONSORT publication standard

The preceding comments represent one review of a few very specific points in the paper concerning the phase 2 minocycline clinical trial for FXS. Fortunately, after decades of clinical trials, experts have produced standards for what information about clinical trials should be published, including with respect to outcomes. Perhaps the preeminent of those standards is known by its acronym, CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials). The purpose of CONSORT is completely germane to the FXS trial examples discussed in this post:

“to alleviate the problems arising from inadequate reporting of randomized controlled trials”.

“The main product of CONSORT is the CONSORT Statement, which is an evidence-based, minimum set of recommendations for reporting randomized trials.

(http://www.consort-statement.org/; emphasis added).

As stated in the most recent CONSORT statement of 2010:

“… randomised trials can yield biased results if they lack methodological rigour [1]. To assess a trial accurately, readers of a published report need complete, clear, and transparent information on its methodology and findings. Unfortunately, attempted assessments frequently fail because authors of many trial reports neglect to provide lucid and complete descriptions of that critical information.” [Schulz2010; emphasis added].

CTgov does require some descriptive trial information to be reported in a manner very similar to CONSORT. In fact, CTgov itself notes that a trial’s description of participant flows is “Identical in purpose to a CONSORT flow diagram, but represented as tables.” (http://prsinfo.clinicaltrials.gov/results_definitions.html)

Our concerns focus on the reporting (or lack thereof) of trial outcomes, including associated statistical information.

The “CONSORT checklist of information to include when reporting a randomised trial” can be used to assess the Leigh2013 paper. In general, the required information was presented, with a few exceptions, including those noted below. In addition, there were also some points for which more specific information would have been desirable. The CONSORT checklist item numbers will be used in the following list of comments:

4a Eligibility criteria for participants

“Inclusion criteria included a diagnosis of FXS confirmed by FMR1 DNA testing, age between 3.5-16 years and a stable regimen of pharmacological treatment for at least 4 weeks prior to study entry. Both male and female individuals were included. Exclusion criteria included those who were previously treated with minocycline, plan to change pharmacological intervention during the study or had an allergy to minocycline or tetracycline. There were no exclusions for concomitant medication use.” [Emphasis added.]

Comment: This is an area of significant interest for this series of posts, since a major goal is to assess whether preclinical animal models would have shown an effect with the treatment drug while already taking other medications. The phrase “a stable regimen of pharmacological treatment” would not allow such as assessment, which is why some researchers try to obtain patient-level data from the trial sponsors.

23 Registration number and name of trial registry

Comment: The NCT registration number does not appear in the Leigh2013 paper. Since ClinicalTrials.gov has an automated program to search for such NCT numbers in research publications, it could be that an author oversight led to the absence of a link to this publication on CTgov.

No explicit statement regarding adherence to CONSORT clinical trial reporting standards was present in the author guidelines for the journal in which the Leigh2013 article was published (Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics), nor did the journal respond to requests for comment as to whether CONSORT standards were followed.

The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) also has requirements for clinical trial registration and recommendations for data presentation:

“Briefly, the ICMJE requires, and recommends that all medical journal editors require, registration of clinical trials in a public trials registry at or before the time of first patient enrollment as a condition of consideration for publication.” …

“Secondary data analyses of primary (parent) clinical trials should not be registered as separate clinical trials, but instead should reference the trial registration number of the primary trial.

The ICMJE encourages posting of clinical trial results in clinical trial registries but does not require it. The ICMJE will not consider as prior publication the posting of trial results in any registry that meets the above criteria if results are limited to a brief (500 word) structured abstract or tables (to include patients enrolled, key outcomes, and adverse events).

The ICMJE recommends that journals publish the trial registration number at the end of the abstract. The ICMJE also recommends that, whenever a registration number is available, authors list this number the first time they use a trial acronym to refer either to the trial they are reporting or to other trials that they mention in the manuscript.”

http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/browse/publishing-and-editorial-issues/clinical-trial-registration.html (Emphasis added.)

From the preceding it can be deduced that the journal in which the minocycline trial results were discussed (Leigh2013) was not following ICMJE recommendations regarding presentation of clinical trial registration numbers.

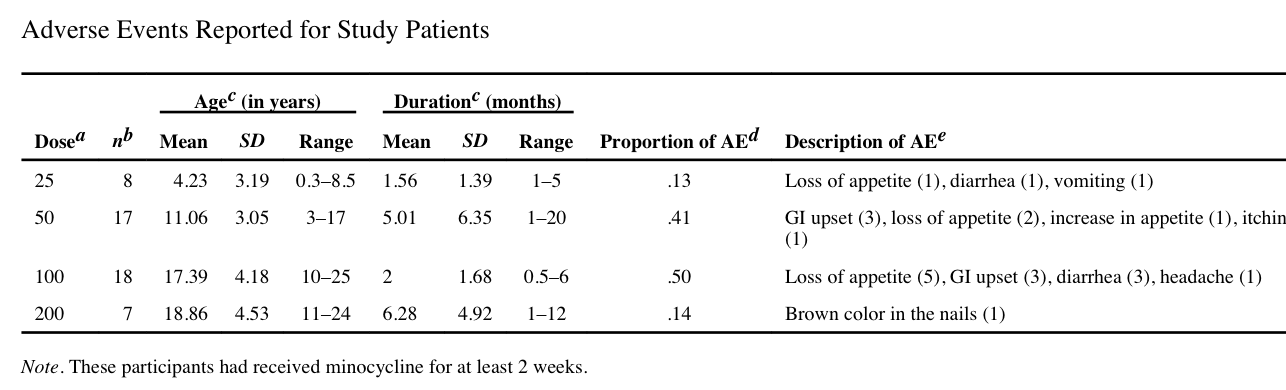

As noted above, there were five other articles found from a PubMed search using the desired search criteria. In those other articles no mention is made of any phase 3 trial which might be planned. One article, by Utari et al., did provide additional information about potential side effects of minocycline use in a Fragile X population followed for two weeks to more than three months. These authors also gave the following warning:

“there is a strong relationship between duration of the exposure of minocycline and lupus erythematosus”

In addition to the tissue discoloration issues noted above in the phase 2 trial, Utari and colleagues also noted a high frequency of gastrointestinal upset:

However, apparently no such difference with the placebo group was observed in the phase 2 trial as reported in Leigh2013 (see comments above).

More specific Internet and PubMed searches

Finally, in order to further assess any mention at all of a phase 3 trial for minocycline in FXS, a general Internet search, as well as a more specific PubMed search, was made for a modification of the original search term.

For simplicity in reading, authors sometimes write clinical trial phases with ordinary numerals, e.g. “3”. However, the formal designation for clinical trial phases uses Roman numerals, e.g. “III”. Unfortunately, PubMed will distinguish between “clinical trial” and “clinical trials”, so both were examined; Google and Bing results were unchanged using single or plural for “clinical trial” or “clinical trials”.

Furthermore, plus signs (“+”) can be used in search engines such as Google and Bing to require the inclusion of the following term in a result; however, PubMed will ignore a plus sign in searches.

In all Internet searches, Google settings were altered to return its maximum of 100 results per page, and Bing web settings were altered to return its maximum of 50 results per page.

Using the search term within the angle brackets, >+”phase II” +”clinical trial” +”Fragile X” +minocycline<, Google returned 10 results and Bing 19 results. Of those, Google specified that three did not include the term minocycline. Google also provided 64 results from Google Scholar, which included those from its regular web and the PubMed searches. However, no indication is given in Google Scholar that all terms appeared in the results.

No mention of a phase III minocycline trial was found (Google and Bing, April 30, 2015), i.e. using >+”phase III” +”clinical trial” +”Fragile X” +minocycline<

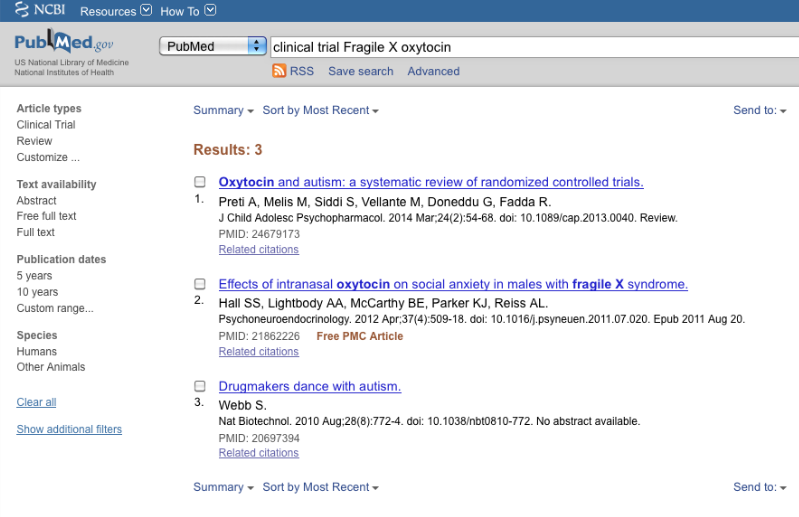

2. >clinical trial Fragile X oxytocin<

The search term of interest produced three results from PubMed (April 28, 2015). One of those was relevant to FXS trials.

As for the minocycline clinical trial report discussed above, this article also fails to reference the NCT identifier number, which probably explains why no link was found to it on CTgov.

The article was published in the journal Psychoneuroendocrinology, which, in contrast to the journal in which the minocycline trial article was published, does have specific information for authors publishing clinical trials. Specifically, authors are informed that:

“Reporting clinical trials

Randomized controlled trials should be presented according to the CONSORT guidelines. At manuscript submission, authors must provide the CONSORT checklist accompanied by a flow diagram that illustrates the progress of patients through the trial, including recruitment, enrollment, randomization, withdrawal and completion, and a detailed description of the randomization procedure. The CONSORT checklist and template flow diagram can be found on http://www.consort-statement.org.”

This means that the reader should be able to move through the article with the CONSORT 2010 checklist to find information and data of interest.

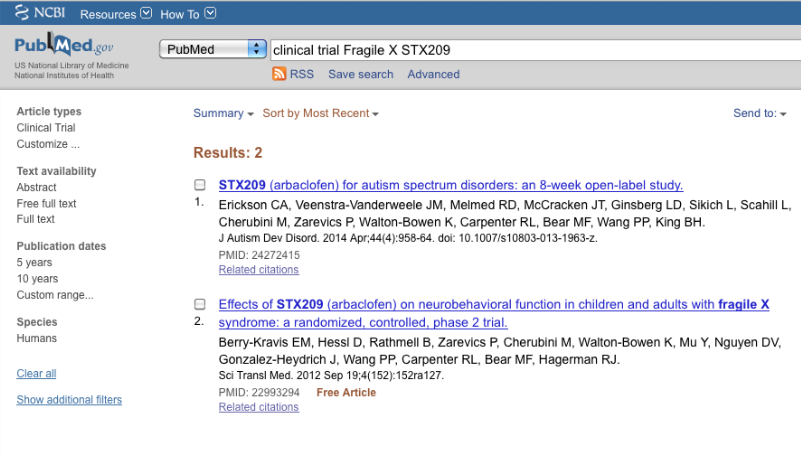

3. >clinical trial Fragile X STX209<

The second FXS found with results on CTgov involved the drug arbaclofen (STX209; NCT00788073). A PubMed search was performed for the search term indicated at 2. Only two results were obtained (April 28, 2015):

For the STX209 trial, a general Internet search showed the following comment from the trial sponsors:

“In fact, in our Phase 2 clinical trial, we observed statistically significant improvements in social avoidance, a core symptom of fragile X syndrome that is characterized by behaviors such as preference to be alone and being withdrawn or isolated. Social avoidance is also a core symptom of autism spectrum disorder, suggesting STX209 could have a positive effect in this larger patient population. Together, these results support our continued development of STX209, which is currently enrolling patients in a Phase 3 study in fragile X syndrome and recently completed enrollment in a Phase 2b study in autism spectrum disorder.” (http://dcru.org/about-us/news/dcru-housed-study-results-published-treatment-fragile-x-syndrome)

“Jul 26, 2010 – Seaside Therapeutics, Inc. announced today data from the largest randomized, placebo-controlled study conducted to date in individuals with fragile X syndrome. In a Phase 2 study of STX209, clinically meaningful improvements on global and specific neurobehavioral outcomes were observed in the general study population. The improvements were statistically significant in pediatric patients with more severe impairments in sociability — a core symptom of fragile X syndrome. STX209 is a selective gamma-amino butyric acid type B (GABA-B) receptor agonist.” (http://www.drugs.com/clinical_trials/seaside-therapeutics-reports-data-randomized-placebo-controlled-phase-2-study-fragile-x-syndrome-9866.html; emphasis added)

From the company’s announcement, we also learn some caveats:

Per Protocol Population:

In the per protocol population of 54 patients, STX209 consistently showed a positive trend for all global measures, including investigators’ assessments of Clinical Global Impressions of Improvement (CGI-I) (p=0.18) and Severity (CGI-S) (p<0.10) and investigator (p<0.10) and caregiver treatment preference (p<0.10). One third of the treatment population was noted as “Much improved” or “Very much improved” on the CGI-I scale, whereas placebo scores were clustered around “No change.” While improvement was noted on the Irritability subscale of the Aberrant Behavior Checklist (ABC-I), the study’s primary endpoint, the magnitude was comparable to that observed on placebo and did not achieve statistical significance.

Low Sociability Population:

Social withdrawal is a core symptom of fragile X syndrome. In the STX209 study, 15 pediatric patients presented with more severe impairments in sociability at baseline. In these patients, STX209 treatment was associated with statistically significant improvements on all global measures, including CGI-I (p<0.01), CGI-S (p<0.05), clinician (p<0.01) and parent/caregiver (p<0.01) preference, as well as improvements on two widely-used measures of social function—the Aberrant Behavior Checklist-Social Withdrawal (ABC-SW, p=0.05) and the Vineland Play and Leisure (p<0.10). In the responder analysis, responders were defined as those subjects with a score of “Very much” or “Much improved” on the CGI-I scale and with a 25%+ improvement on the ABC-SW. When applying these rigorous criteria, more than 50% of subjects showed a positive response while taking STX209, versus just 13% on placebo (p=0.05).

Of course, having read the preceding interpretations, which were not even summarily reviewed on CTgov, nor in any research publication found on PubMed, the natural inclination would be to look for the phase 3 STX209 trial.

Unfortunately, when we search CTgov for STX209 Fragile X phase 3 trials, we find three (as of April 15, 2015). Two examined the most positive of the effects from the preceding phase 2 trial – a reduction in social withdrawal. The first had adolescent subjects and was completed in December 2012; the second had pediatric subjects and was completed in June 2013. Neither showed results. The third trial was an open label extension that was “terminated”.

Therefore, the availability of clinical trial results is at present quite haphazard, despite the promise of databases such as ClinicalTrials.gov. Recommendations we have made to NIH for improvements to ClinicalTrials.gov will be presented following a further examination of legal standards and corporate policies that exist in the U.S. and in the European Union with respect to clinical trial data availability.